The areas of bare sand characteristic of central Australia provide a natural drawing board permanently at hand. Since any continuous conversation is generally carried on by persons sitting on the ground, marking the sand readily becomes a supplement to verbal expression.

Walbiri often contrast their own mode of life with that of the white Australian’s by remarking with pride, “We Walbiri live on the ground” […]. They regard sand drawing as part of this valued mode of life, and as a characteristic aspect of their style of expression and communication. To accompany one’s speech with explanatory sand markings is to “talk” in the Walbiri manner.

[…]

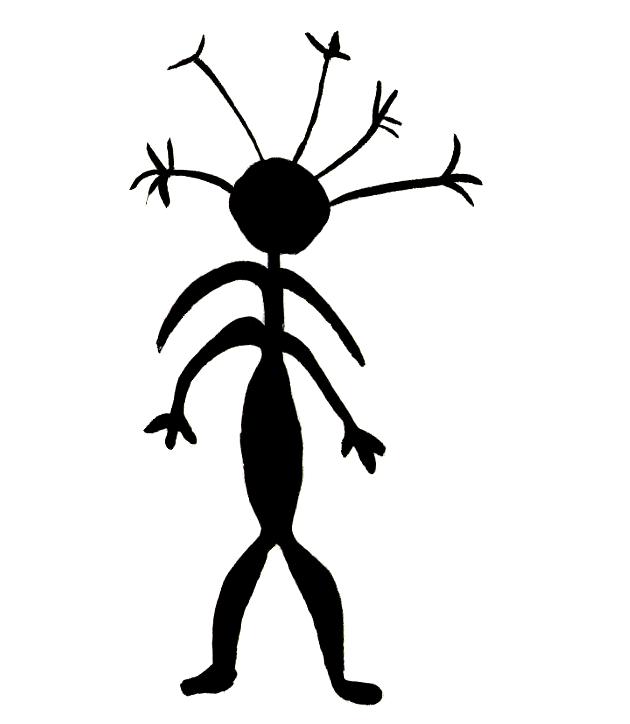

Both men and women draw similar graphic elements on the ground during storytelling or general discourse, but women formalize this narrative usage in a distinctive genre that I shall call a sand story. A space of about one to two feet in diameter is smoothed in the sand; the stubble is removed and small stones plucked out. The process of narration consists of the rhythmic interplay of a continuous running graphic notation with gesture signs and singsong verbal patter. The vocal accompaniment may sometimes drop to a minimum; the basic meaning is then carried by the combination of gestural and graphic signs. The gesture signs are intricate and specific and can substitute on occasion for a fuller verbalization.

Walbiri call stories told by women in this fashion by the term for any traditional story about ancestral times, djugurba. They point out that only women tell stories in this manner, although all Walbiri are familiar with the method. While the technique is elaborated most systematically in narrations of events ascribed to ancestral times, women also use it in a more fragmentary way to convey personal experiences or current gossip. As a mode of communication it can be activated in narration generally, irrespective of whether the content is supposed to refer to ancestral times or the present. A “proper” djugurba, however, is thought to refer to ancestral events.

The social context of storytelling is the casual, informal life of the camp, unhedged by secrecy or ritual sanctions. The women’s camps are a common location. […] Even in the hottest weather the women tend to sit close together; without changing her position or making any special announcement, a woman may begin to tell a story. Occasionally an older woman can be seen wordlessly intoning a story to herself as she gestures and marks the sand, but ordinarily a few individuals in the group will cluster around the narrator, leaving whenever they wish regardless of whether the story is finished or not. At any time the narrator herself may break off the story and go on to perform some chore, or evengo to sleep in the process of narration.

[…] Each woman had a fund of stories that she may have learned from any female kin or from her husband. When asked, women sometimes suggested that tales should be transmitted from mother to daughter, but in fact there are no specific rights over these stories; as women said, “everybody” teaches them these tales.

Walbiri children do not tell sand stories as a pastime, but at the age of about five or six they can make and identify the basic graphic forms used in narration. […] A small child or baby may sit on its mother’s lap while she tells a sand story; the observation of sand drawing is thus part of early perceptual experience. Sand drawing is not systematically taught, and learning is largely by observation.

At the age of about eight or nine, a child can quite readily tell narratives of his or her own invention. As a girl grows older, she becomes increasingly fluent in storytelling and may use the sand story technique (largely without gesture signs according to my observation) to communicate narratives about personal experiences or that she has herself invented. She may occasionally tell such tales to other girls or younger children. Older boys are more reluctant to use the technique since it is identified with feminine role behavior.

Nancy D. Munn, Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society, Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1986, pp. 58-64

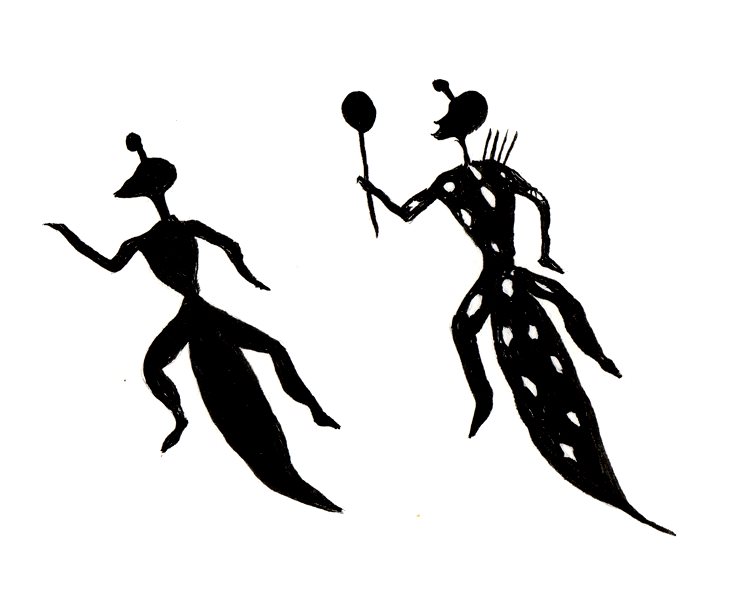

Illlustration inspired by Bushman rock paintings in the Cederberg, South Africa