At the end of a tale in one of my notebooks from Co. Clare I wrote: “30 December 1929. This is the worst told tale I have ever heard, and to one familiar with the story the omissions, hesitations and inconsistencies were exasperating. The audience was quite disgusted.

Now and then I would catch the eye of John Carey, a good story-teller, who was sitting beside the fire smoking, and he would shake his head sadly. To him it was sacrilege to mishandle a story so. The unfortunate reciter, who was really doing his best, used to cough at times – he had a cold, but it suited him to cloak his deficiencies with a loud cough now and then, and the resting place in the narration thus created allowed him to think. Very often, storytellers cough when they are not sure what they are going to say!

Finally, old Carey could stand the strain no longer, being outraged beyond endurance, and he shouted at the story-teller telling him what he had omitted and admonishing him! Carey and the other listeners had known the reciter’s father, who was the best story-teller in the district; the son remembered the tales, but could not tell them properly.

The illiterate literary critic can be as merciless in his judgement as his sophisticated colleague writing in a room full of books, and we can be assured that medieval as well as modern oral narrative had to pass through the purgatorial fire of many centuries before reaching the high standard required of it by the cynical critics of the Gaelic-spaking world.

Seamus O Duilearga [James Delargy] “Irish Tales and Story-tellers”, in H. Khun and K.Schier (eds.), Märchen, Mythos und Dichtung: Festschrift zum 90. Geburtstag Friedrich von der Leyens am 19. August 1963, Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1963, pp. 66-67

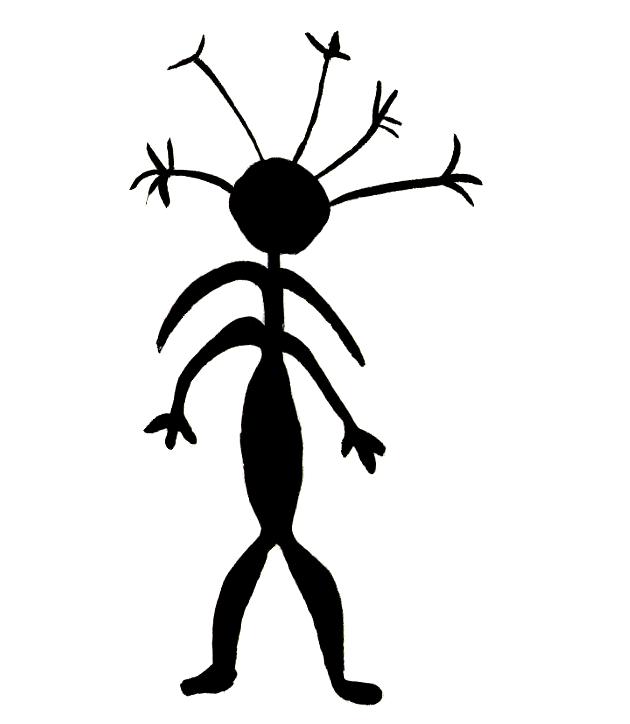

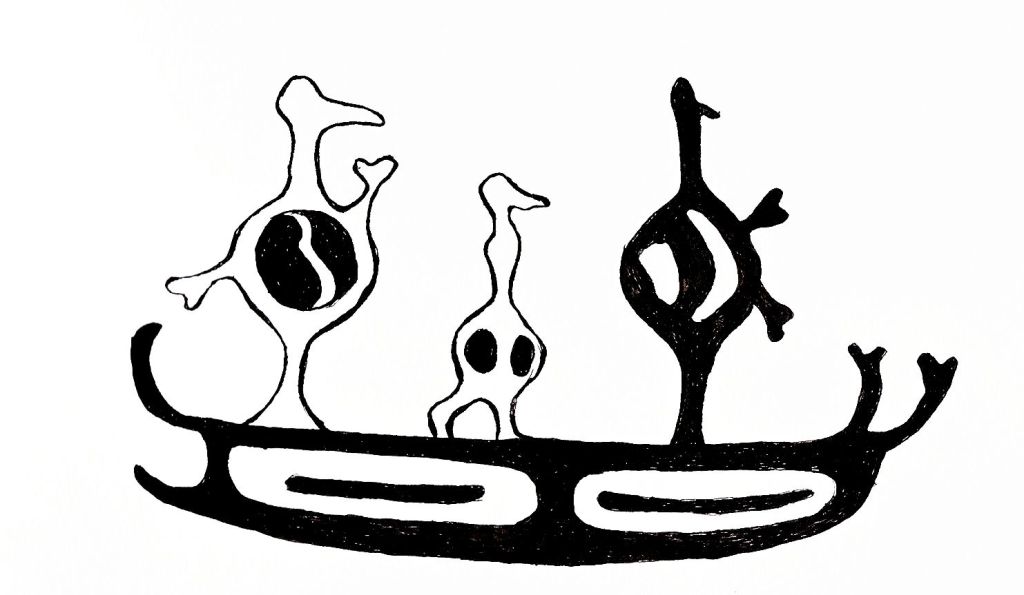

Illustration inspired by the drawing of a shaman’s drum